Earlier today, I read a rather troubling news

story about a new weapons system that has been developed by the US military and is being introduced in Iraq later this spring:

The US Army will by June deploy in Iraq its "Matrix" system of remotely-detonated landmines, despite widespread concerns about the technology. The Mosul-based Styker Brigade will, according to Yahoo! news, be able to control individual devices from a laptop via a WLAN set-up. The Army reckons Matrix will eliminate accidental deaths caused by dumb landmines. Critics say otherwise.

Following successful tests in September, the US will deploy 25 sets of mines in Iraq. These include both M18 Claymores, which deliver steel balls, and the "M5 Modular Crowd Control Munition" - a non-lethal rubber-ball-delivering alternative. The Army's Picatinny Arsenal in New Jersey said in a January statement that Matrix was intended for "firebase security, landing zone security, remote offensive attack and both infrastructure and check point protection".

On reading this article, one word stands out for me: WLAN (which is short for Wireless LAN). As a technology professional and a network security expert, that word scares me. While commonly used, WLAN technology (also known as 802.11a, 802.11b and 802.11g wireless Ethernet) has a number of very serious security issues associated with it. In my job as an IT director, I have banned WLAN technology from our corporate network, and I find it shocking that the US army would use this same technology as the basis for such a critical function as controlling landmines.

For me personally, I also find it troubling that the first place they are deploying these things is Mosul, the same city a few of my online blogger friends live in. Knowing what I know about this technology, I don't like imagining them walking past these WLAN-enabled Claymore mines on the way to school or work.

There are four basic reasons for my concern:

Reason #1: Interference with other common devicesWLAN (802.11b and 802.11g) uses a radio frequency of 2.4 gigahertz (GHz). What a lot of people don't realize is that this frequency is not reserved for WLAN use - it was part of a block of radio band that was set aside for unregulated public use. Anyone in the public can use this frequency for anything they want. And, while WLAN is a common user of this frequency, it's not the only user. Some common household appliances also use a 2.4 gigahertz frequency:

- Cordless phones

- Microwave ovens

- Baby monitors

- Wireless cameras

- Other WLAN networks

Any of these devices can cause interference on a WLAN network. This interference can introduce errors in the wireless network, impeding it, or blocking it from carrying data at all. For a landmine system, this could mean that the system could be rendered inoperable by radio interference on the 2.4 GHz band.

The ready availability of household appliances using this band also means that a terrorist could exploit this knowledge to make an effective jamming apparatus from a household appliance. For example, knowing that a microwave oven cooks food with 2.4 GHz radio waves, an enterprising terrorist could disassemble the microwave, take out the microwave emitter, and create a simplistic but effective jamming device that could potentially disable the communication with the landmines and prevent them from detonating.

Reason #2: Ease of entry for hackersWLAN cards are readily available, and only cost about $40. And, the WLAN technology and its encryption algorithms are well understood. What's more, while a normal WLAN connection can only travel a short distance, a directional antenna (yagi or parabolic dish) can allow a hacker to connect to a WLAN from up to two miles away! And, a crude yagi antenna can be constructed from a

Pringles can with wire wrapped around it.

The army had better hope that there are no software bugs or other security flaws in the technology, because by using an open technology like WLAN, they are giving any hacker with a WLAN card within radio range a chance to find out for themselves. Since we all know that there is no such thing as bug-free software, the possibility of a hacker finding a bug in this system is particularly worrisome.

Reason #3: Basic security flaws in the technologyThe original WLAN security framework was built around an encryption protocol called Wired Equivalent Privacy (or WEP for short). Since the release of WEP, a number of severe and insurmountable security flaws were found in it, and since then, a number of hacking tools (AirSnort, WEPCrack, etc.) have been released, which allow a hacker to break the underlying WEP key and gain access to the wireless network.

Since then, a newer security technology called WPA has been released, and while it does address all the security flaws in WEP, it is still new enough that it is difficult to fully feel comfortable with it.

Reason #4: Static keysAnother security flaw, which I suspect would be present in this system, is static keys. WPA (like WEP) generally depends on a static password, or "key" that is configured into all the WLAN enabled devices on a network. If a device does not know the correct key, it will not be able to communicate, and other devices will not communicate with it.

In a WLAN network, all of the devices on the network have to be programmed with the same key to allow them to talk to each other. But, this means that if a hacker is able to figure out the static key, he/she can decrypt all of the information going back and forth in the network, and can also launch a number of very dangerous hacks known in the computer security world as "man-in-the-middle" attacks:

- Password sniffing: capturing passwords and other authentication credentials as they cross the network.

- Session hijacking: kicking the real user off, and taking over his/her session.

- Spoofing: tricking a device on the network into thinking the hacker's laptop is another device on the network.

ConclusionA basic requirement of a landmine control system is that it is reliable: landmines always go boom you press the button, and never go boom if you haven't pressed the button. WLAN does not provide this guarantee. If someone in a nearby house is using a baby monitor, a microwave oven, or cordless phone, or if a terrorist intentionally tries to jam the frequency, it could cause enough interference with the system to prevent it from working when the soldiers are counting on it.

A far worse scenario would be if a cyberterrorist hacker could figure out how to break into the system and use it against American troops. Imagine a terrorist with a laptop computer waiting for an American soldier or civilian to walk in front of one of these Claymore mines, and with one hit of the "enter" key on his laptop: ka-

BOOM. Not a very pleasant thought...

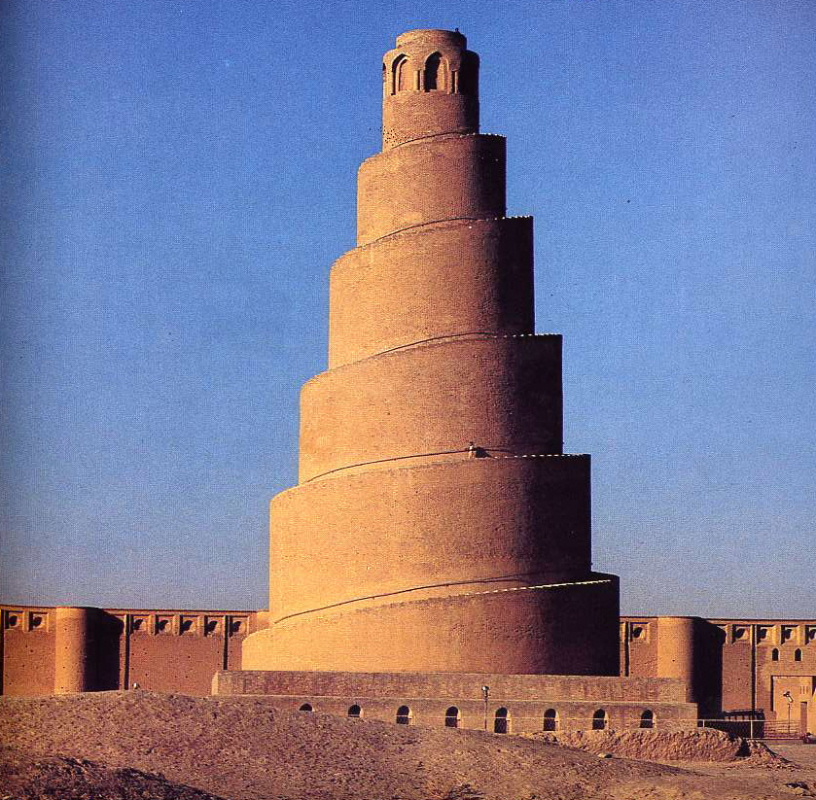

Claymore mines have been around for a long time - they were invented in the 1950s, and were used by the United States in the Vietnam War. They are a specially shaped mine (shown below) with a directional charge that is designed to blast an enemy in front of it with shrapnel, while not harming those behind it. A normal Claymore is connected to a remote detonator using a wire (like you see below), which may be cumbersome, but it does pretty much guarantee the Claymore will detonate when you press the button, and is not susceptible to outside interference since it is connected to that button with a wire.

A Claymore Mine

With "Matrix", the Claymore is the same, but the certainty that comes with having a hard-wire connection to it is removed, and replaced with a less certain wireless WLAN connection.

In summary, I am concerned that an unreliable and hacker-prone technology like WLAN is being used to control something as critical as a Claymore mine. Claymore mines are defensive weapons - when they don't go off when they're supposed to, the soldiers behind them who are counting on them as a defensive measure die. And, when they do go off when they're not supposed to, anyone in front of them dies.

A house built on a foundation of rock will last for generations, while one built on a foundation of sand may not last through the next storm. Likewise, a weapons system based a foundation of reliable and proven technology will be dependable, while a weapons system based on a weak and flawed technology foundation may fail you at the most critical moment. WLAN, unfortunately, falls into the latter category.